Accessibility is Always a Good I.D.E.A!

During my undergrad years at UC Santa Cruz, I worked as an after-school educator in a middle school in Watsonville. I drove down scenic California Highway 1 three times a week and assisted sweet, giggly third graders with their English and math homework.

One young woman, whom we'll refer to as Leila, was having trouble with her multiplication tables - specifically multiplying by 11s. The rest of the group sighed with frustration that Leila could not figure it out. "It's so simple," one of my more academically astute students cried, yanking her head back in exhaustion. I reminded her that what is simple for her might not be as easy for other people. Leila smiled at me, but I could tell that she was nervous and maybe a little embarrassed. We worked on it more after recess, away from the other girls.

When Leila was away from her peers' pressuring eyes, she excelled and picked it up much more quickly. At the end of the day, before she walked out of my classroom, she admitted that she was happy to learn her 11's, because she "didn't want to slow everyone down." I weakly smiled as she left with newfound confidence. I still think about Leila, especially when we talk about accessibility, or the act of creating equality between people of all levels of ability.

One in seven individuals worldwide has a disability, including people whose disability is related to mobility, mental health, sight, hearing, flexibility, memory, or intellectual development.

Disabilities are visible and invisible, temporary and chronic. To create a world that truly works for all, we must include disability justice in the realm of diversity, equity, and inclusion education. To function in an organization or community, people need to feel psychological safety - like the systems in place to serve others are also built to function for them the same as it functions for others. Like all of the other changes that we want to see in our community, we must start from the self and move to systems.

Let’s Talk About Disability Justice in the Workplace

I'm a non-disabled person, which means that I often don't think twice about daily tasks such as walking, reading, or writing. I don't require a wheelchair or crutches to get around, and I don't have a neurodiversity that makes it more challenging to communicate. As a non-disabled person, it is my responsibility to support a greater awareness of disabled experiences by having conversations with other “ableds”- much like the conversation around white allyship. To dismantle the oppressive hierarchal systems that work against people with disabilities, non-disabled people must address their inherent ableism. Here are the steps I took to address ableism within myself.

Do your research

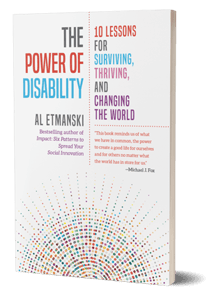

Nomenclature for disabled communities is continually changing. Author of The Power of Disability, Al Etmanski, is the parent of a young woman with Down’s Syndrome. He notes that there aren't any catch-all terms for referring to people at different levels of ability. "In most cases, it depends on context and personal preference," he writes.

Outside of identification, there are many benefits to being well-versed in the dynamic world of accessibility justice. But if it’s curiosity that drives you to learn more, take the initiative to do independent research, like this resource on disabled allyship from the University of Illinois. Frequently the task of educating others about their illness could be laborious and cost them energy.

If you want to be an ally and eventual community changemaker, you will have to take the initiative to be knowledgeable about different levels of disability to challenge your own biases - and, hopefully, the prejudices of others.

Identifying your Subtle Acts of Exclusion

A Subtle Act of Exclusion, otherwise known as a microaggression, is described by authors Tiffany Jana and Michael Baran as the "subtler everyday actions that normalize exclusion" that do a lot of damage but can fly under the radar. You can combat these SAEs by approaching every situation with empathy and education. As Jana and Baran write in Subtle Acts of Exclusion, “a lot of the subtle acts of exclusion that happen to these folks happen because of a lack of closeness, of familiarity, of basic understanding.”

Look closely at your vocabulary

If you’re wondering about an easy, quick way to eliminate ableist SAE’s from your life, a good first step is to examine and remove harmful language from your vocabulary. As Etmanski writes in The Power of Disability, “Focus on your impact, not your intent.”

Even if you’ve been saying certain words for years and you didn’t know that they were harmful, they could have been harming the people around you. Once you've identified your subtle acts of exclusion, challenged your biases, and removed damaging language from your vocabulary, it’s time to move out of the self and into mindful personal interactions.

Put people first

Utilizing the research and self-examination skills learned in section one will show you the value of effective and empathetic communication. How we interact with each other has a strong effect on our psychological safety, so compassionate communication is our responsibility as changemakers, leaders, and humans. Communication also helps us build closer bonds with the people around us.

According to the author of The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety, Tim Clark, communication can be a stepping stone for greater emotional welfare. "The faster and deeper you get to know each other, the more effectively you can work together. More contact and context tend to create more empathy." Insensitive interpersonal communication works the opposite way, especially for people with disabilities. Here's how to position yourself as an ally to people of varying cases of ability.

Check your condescension

Much like non-disabled people, many people with disabilities dislike condescending and pitying remarks. Many will say that they want to be spoken to like everyone else. For example, praising a disabled person for performing routine tasks might seem like you're offering support, but people with disabilities could perceive that the expectations for them are low.

As Jana and Baran write in Subtle Acts of Exclusion, “At the heart of it, people with disabilities are asking just to be treated normally with normal expectations. One man who has low sight explained that as he was exiting the restroom at work, a colleague held the door open for him. As he walked through the door, the colleague said, ‘Good job, buddy.’ He explains, ‘If his expectations of what I could do are so low that he thinks I need praise for walking out of the restroom, what are his expectations for me actually performing my job?’"

Ask before you act

As my mother used to say, "Don't assume; it just makes a behind out of you and me." I might have cleaned up the language a little, but the message stays the same: you should never assume that someone needs your help to do things they do every day. Don't grab and push people using wheelchairs without their permission. Don't finish the sentence of someone with a stutter. If you suspect that someone might need help but you aren't sure, ask. Create an environment in which people with disabilities feel comfortable asking for what they need, and they will be happy to do so. As Jana and Baran write, "A simple ‘Anything I can do to assist you?’ goes a long way instead of assuming that people can’t do something on their own or assuming that you know what kind of assistance they must need.”

Learn to listen

You know that feeling when someone is talking to you, but you've been so busy thinking of a brilliantly witty response that you missed a whole chunk of what they were saying? That feeling is pretty universal, but it helps to put it in check when you see it coming.

You know that feeling when someone is talking to you, but you've been so busy thinking of a brilliantly witty response that you missed a whole chunk of what they were saying? That feeling is pretty universal, but it helps to put it in check when you see it coming.

Listen for learning, not just to hear yourself talk. If you're listening with the focus on your side of the conversation, you aren't learning anything. If you have able-bodied privilege, you will likely make mistakes on your journey towards being an ally. Lean into the discomfort, and learn from it. As a rule of thumb for person-to-person interactions, Jana and Baran offer these words of advice: “Treating people as normal, not making assumptions, and asking questions can go a long way toward making people of varying abilities feel included, at work and in other contexts.”

Accessible Systems for All

Once you’ve reflected on yourself and your communication style, it’s time to focus on the ultimate goal of the movement for disability justice: to create a society that is equally accessible to disabled people as it is for disabled people. Accessibility should be commonplace and available for everyone as a permanent part of the larger societal systems to support people. The accessibility movement's goal is to create a society that is equally as accessible for disabled and abled people alike. Here are some steps that will help you move from allyship to accompliceship by eliminating systemic injustice.

Advocate for accessibility and Disability Justice in organizations

If you’re in a position of influence in your organization or community, there are things you can put into immediate effect that will advocate for people who need accessibility. The ideal situation for people with any disability (and without) is, without a doubt, free universal healthcare. While we wait for the government to catch up with this idea, you can do your part to invest in adequate healthcare for the people in your organization.

If you aren't in a position to make those kinds of hefty changes, you can still advocate for physical and technological support such as ramps and ESL translators and knowledge on how to best support people with disabilities. Disabled people are not the problem. The problem is the lack of accessibility for them. As Lily Zheng and Inge Hansen write in The Ethical Sellout, “The social model of disability considers barriers to access the primary issue. The solution is to address inaccessible environments, discrimination and prejudice, and problematic organizational practices and procedures."

If you are in a position of power in this company, do not wait for people to ask you for things they need to do their jobs. Make accessibility the norm, not a “special” needs issue. Think about what your most marginalized employee needs to do their job, and make it accessible to everyone.

Include accessibility in your Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) training

In The Body is Not An Apology, author Sonya Renee Taylor remarks that disability justice is an essential aspect of inclusion because many people have disabilities and are also a part of other marginalized groups. “Similar to fatphobia, activist spaces often erase the needs of the disability community, fighting for the rights of LGBTQIA+ and/or people of color, while forgetting that many of those people are or will be disabled. Activism absent of the voices and vision of disabled people cannot be radical.” There is no possibility for an intersectional community society without talking about accessibility. Pursue intersectional equality through learning together.

Challenge the status quo

This seems like a big task, and that’s because it is. Toppling an entire system of inequality is not a job you can do alone, but it is a job that everyone must do for it to work. As Sonya Renee Taylor writes in The Body is Not An Apology, you can start by challenging casual ableism - like calling out your friend’s behavior when they use unempathetic terms. “Invite those you love to be part of raising awareness and action to be in greater solidarity with disabled communities.” It will be uncomfortable to challenge the people you love, and they might feel uncomfortable too. Discomfort is required to grow. There is no way around it. Challenging the status quo means being willing to be uncomfortable to make the world a better place.

Making the World a Betta (and More Accessible) Place

As Leila left my classroom that day, I smiled weakly because something in my gut didn't feel right, but I couldn't place it. It took me several years to realize that I felt unsatisfied because I didn't want her to excel out of fear of slowing down her classmates. I wanted her to excel for her own sake. When the pressure of conforming to others' needs was removed, Leila was able to focus on her own needs and thrived as a result of that accessibility, the same way anyone of us would succeed if all of our needs were met. On our last day of class together, she gave me a betta fish that kept me company throughout much of the following semester. Every time I looked at the fish (whom we named Megatron), I think about her and my other students, who each had different needs, abilities, and strengths, and how all of that contributed to an environment where the kids were able to grow.

When we put aside our egos, prioritize empathy, and work together to challenge systemic injustice, we can do anything - even our multiplication tables.

![[r]-the-four-stages-of-psychological-safty](https://ideas.bkconnection.com/hs-fs/hubfs/%5Br%5D-the-four-stages-of-psychological-safty.png?width=238&name=%5Br%5D-the-four-stages-of-psychological-safty.png)