My previous company was small when I started there, and I was given the freedom and responsibility to grow and manage my own department. That type of trust fosters professional self-confidence. I don’t often feel anxious or shy about sharing my opinions. But not everyone has the luxury of being in an environment that invokes this kind of confidence.

Companies prioritizing DEIJ initiatives want to invest in the growth and acceptance of all employees. Nurturing acceptance and confidence in an employee is the basis of inclusion (the I in DEIJ), which is measured by psychological safety.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion strategist and consultant Lily Zheng defines psychological safety as “the individual, team, or organization-level belief that a given environment is safe for interpersonal risk taking, vulnerability, and failure. It’s a metric by which we measure inclusion.”

Historically, people have been excluded from company social collectives because of race, gender, sexuality, disability, religion, and more. And while a large portion of inclusive responsibility is on the shoulders of those who develop and enforce company hiring practices, inclusion and exclusion happen at the social-interpersonal level.

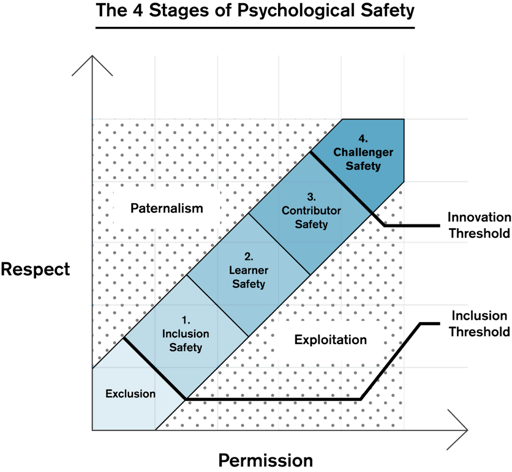

Timothy R. Clark describes psychological safety as a four-stage process in his book The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety.

Diagram from Timothy R. Clark and The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety

Inclusion Safety

Inclusion is the very first step to feeling psychological safety. It is the pure acceptance of a person simply because they are human. The person is accepted into the social collective with no roadblocks. It is the responsibility of companies to ensure their company culture is inclusive at its core, and it is the existing employees’ responsibility to be accepting of everyone.

While inclusivity is paramount, in Ending Checkbox Diversity, Dannie Lynn Fountain describes the double-edged sword that companies encounter:

It is common for the code of conduct to also include language around communications standards or ‘bringing your whole self to work’ ... Instead of specifically defining issues like diversity, equity, and inclusion within the code of conduct, this language creates the expectation for all employees to be treated with dignity and respect and for all employees to bring their whole selves to work—including racist employees.

Learner Safety

The next step of psychological safety is when a person feels comfortable to ask questions, experiment, and make mistakes. People need to feel safe to learn and make mistakes; otherwise, they will remain passive and fearful of taking risks.

In their book DEI Deconstructed, Lily Zheng says, “In a culture with high failure avoidance, few people are comfortable taking risks of their own volition and often make ‘safe’ decisions that are unlikely to fail.”

Companies lacking learner safety are doomed to become stagnant. Innovation comes from risk, and if employees are afraid to take risks, nothing will ever evolve.

Contributor Safety

In the contributor stage of psychological safety, a person feels an expectation to perform their job appropriately and competently without micromanagement. It’s essentially permission and freedom to do your job as you see fit because there is trust.

Jennifer Brown illustrates this stage eloquently in her book How to Be an Inclusive Leader (second edition): “This full human potential and creativity can only be unleashed when we feel like we belong, when we have psychological safety and trust with our colleagues, and when our capabilities aren’t doubted or downplayed because of biases about us.”

Challenger Safety

The final stage of psychological safety gives people permission to challenge the status quo without fear of retribution. This stage gives people the confidence to use their voice when they feel like something needs to change or someone is doing something wrong. Challenger safety gives people the power to resist pressures to conform or stay silent. It is paramount in all DEIJ initiatives. People need to be able to speak up and speak out about anything that doesn’t sit right with them.

I encountered a situation at a previous job where I objected morally to the decisions around the COVID-19 processes in place. I felt as though management was being dishonest and putting people in danger, and I was afraid when I told my boss that it felt wrong and I couldn’t support him. And while I could tell he disagreed with me, I didn’t face any retribution for speaking out.

In her groundbreaking book Emotional Justice, Esther Armah discusses the choice to stay silent in the face of racism:

This notion of choice—of what you choose and what you don’t—it is at the heart of resistance negotiation. Because you’re also really negotiating with your own comfort, you’re negotiating with your own instinct to choose safety rather than struggle. And you’re negotiating with your instinct to stay silent.

Companies with psychological safety allow space for everyone to feel comfortable to speak against racist, offensive, and exclusive speech and actions, regardless of how veiled or coded they may be.

A Fifth Stage: Transparency Safety

I created one more stage: transparency safety. I think it’s incredibly important that organizations and leaders feel empowered to be transparent with DEIJ initiatives, especially failures.

Fountain addresses this in Ending Checkbox Diversity: “Acknowledgment of mistakes is critical. Oftentimes organizations create levers for equity and fail to follow through on communicating when those levers fail. Little or no advancement of representation in hiring, taking incorrect or retaliatory adverse employee action when individuals speak up, or failing to meaningfully investigate harassment claims are all ways that underrepresented employees end up suffering in the workplace—being transparent about the ‘what’s next’ when situations like these arise drives meaningful increases to employee confidence and psychological safety in the workplace.”

Companies need to be honest and transparent with employees. Trying to silence victims, cover up incidents, or hide failures creates distrust and erodes psychological safety. In his book about navigating crises, Reputation Capital, T. J. Winick asks readers to evaluate themselves: “How you engage with those inside and outside your organization is the most straightforward and organic way to influence how others feel about you. Ask yourself: Are you helpful? Are you perceived as honest and trustworthy? Do you keep your promises? If you make a mistake, do you admit as much and hold yourself accountable?”

Psychological safety is the foundation of diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice initiatives. I cannot stress how significant the impacts of acceptance and trust are when creating an environment that supports and encourages confidence and ingenuity.